Rights to Freedom and Justice

Rights to Freedom and Justice

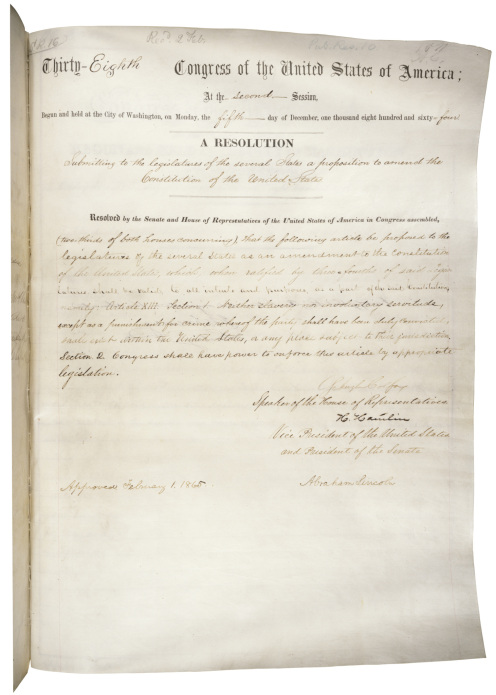

Two of the stated purposes of the Constitution of the United States are to “establish justice” and “secure the blessings of liberty.” Yet the Constitution did not abolish slavery. Some saw this as a contradiction; others believed they should be free to own slaves. The definition and application of the Constitutional ideals of freedom and justice have been the subject of debate since its inception.

THIS SECTION INCLUDES STORIES ABOUT:

- Slavery and other forms of servitude

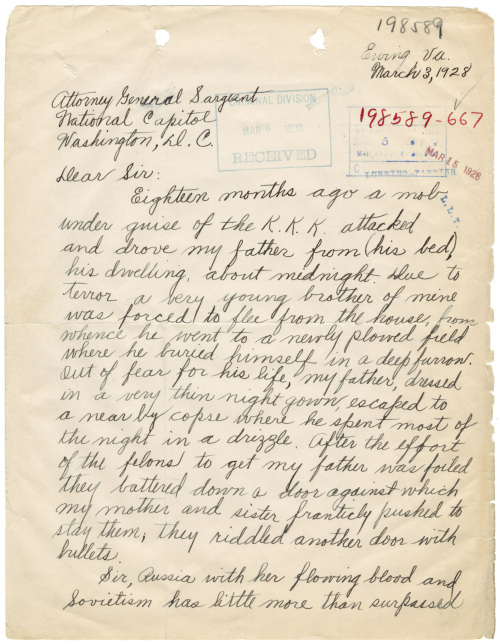

- The Ku Klux Klan and mob violence

- Japanese internment

- Struggles for fair trials

Chapter one

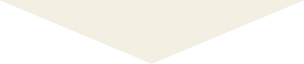

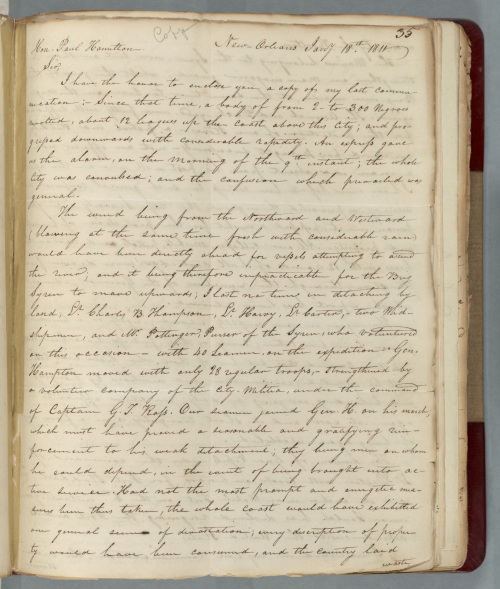

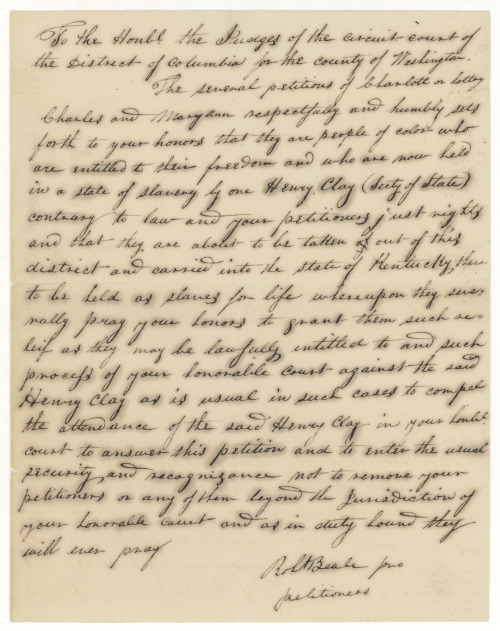

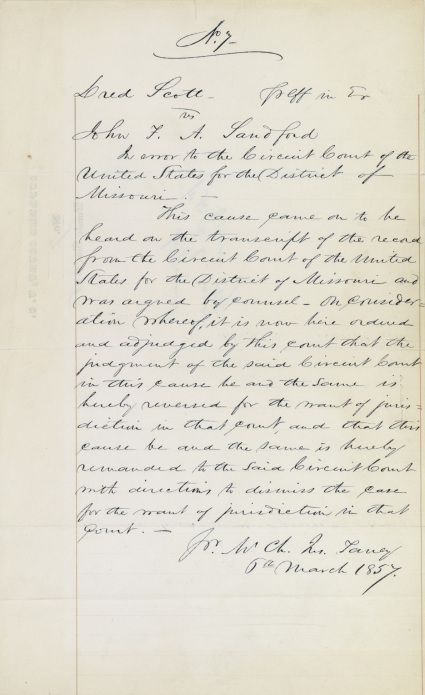

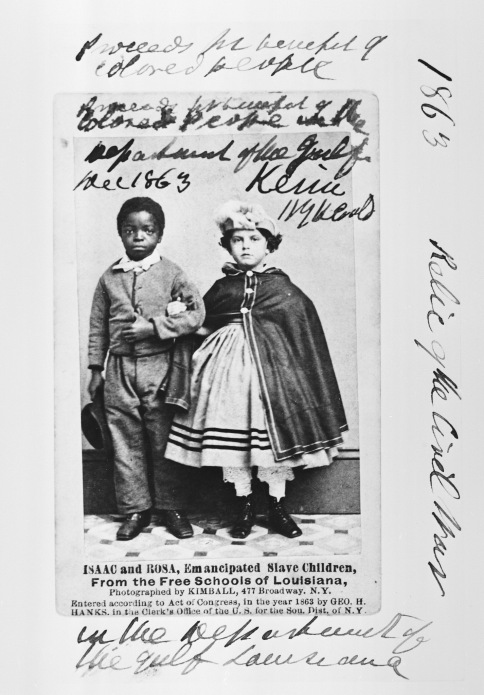

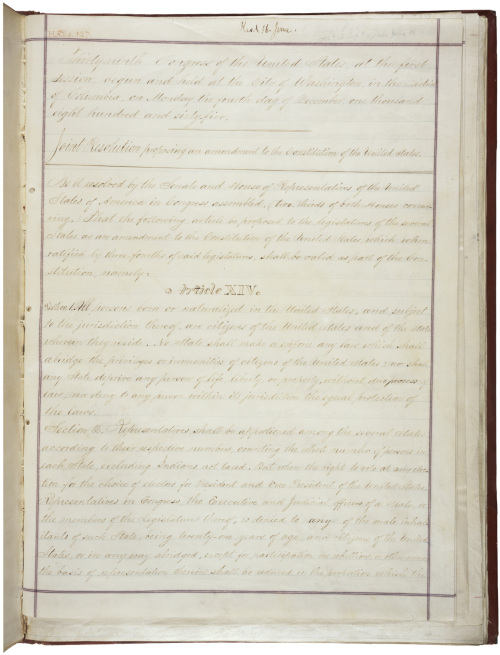

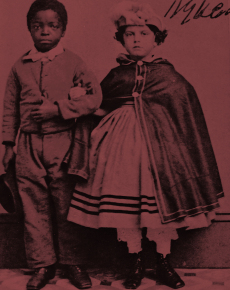

According to Chief Justice Roger B. Taney’s infamous opinion in the 1857 Dred Scott case, “the enslaved African race were not intended to be included, and formed no part of the people who framed and adopted” the Declaration of Independence. In the decades leading up to the Civil War, African Americans battled for recognition of their basic humanity and acceptance as Americans.

Chapter two

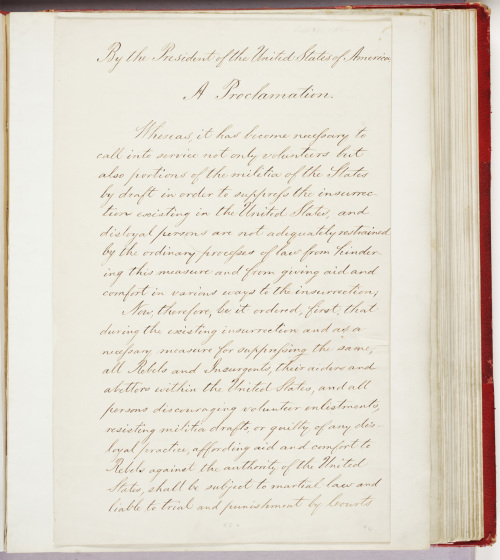

President Abraham Lincoln took actions during the Civil War that restricted Americans’ legal rights. He suspended the writ of habeas corpus twice—denying criminal suspects the right to a trial—and he instituted martial law in volatile border areas. Lincoln believed these measures were necessary and constitutional under his war powers, but many Americans vehemently opposed them.

The Civil War 1861–1865

Chapter three

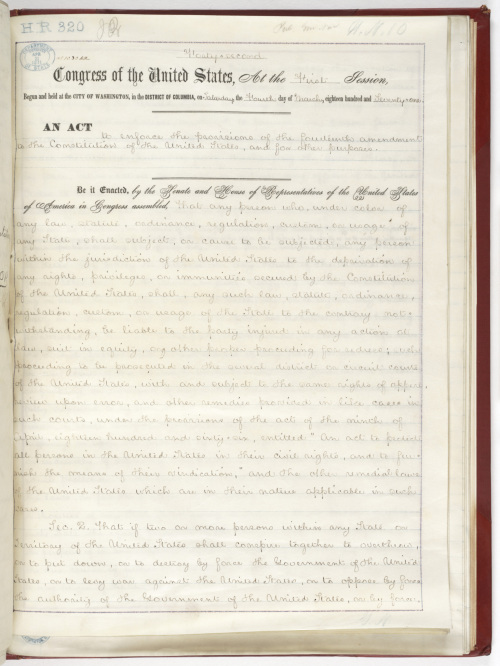

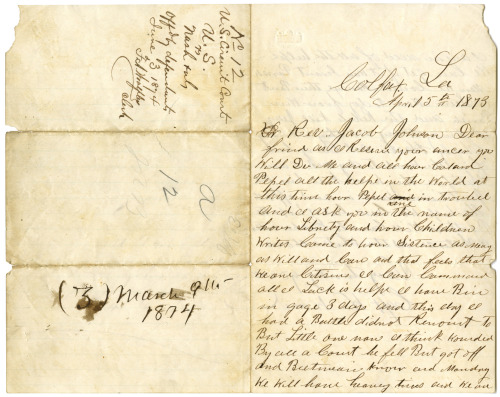

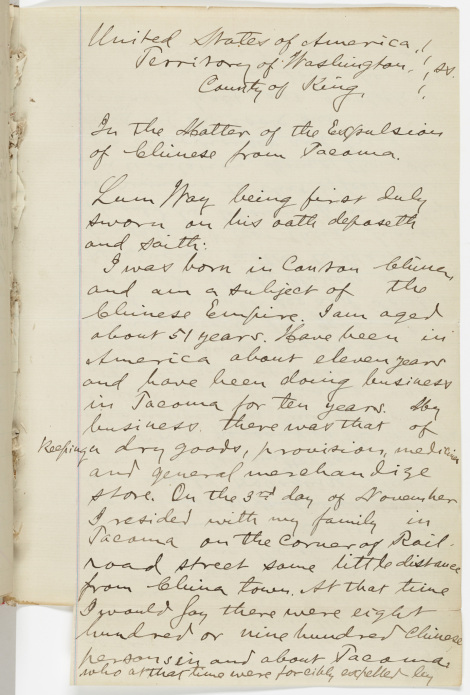

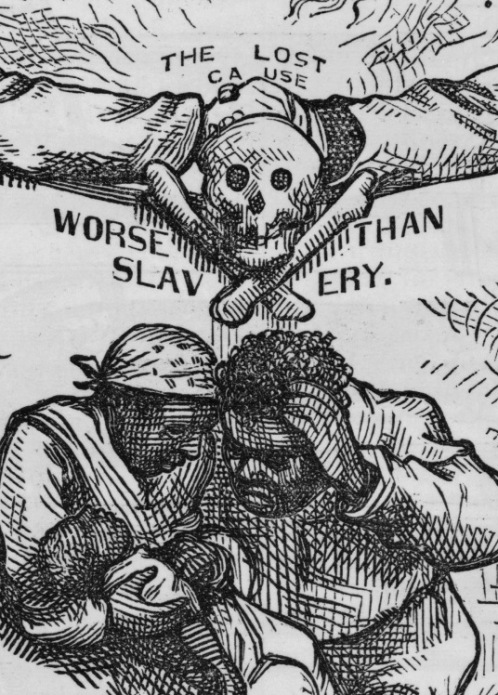

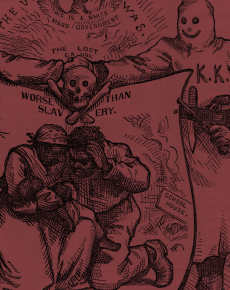

A few years after the Civil War, Southern paramilitary organizations like the Ku Klux Klan reestablished white domination over blacks through a campaign of terror. Southern states passed laws to sidestep the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments. On the West Coast, violence and discriminatory laws targeted Chinese immigrants. Jews, Catholics, and other immigrant groups were also targets of violence.

The Panic of 1873 1873–1879

Chapter four

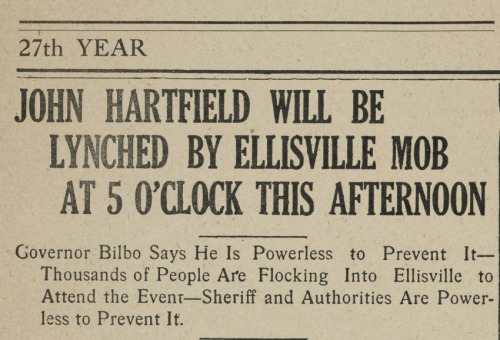

After Reconstruction was abandoned in 1877, Southern states passed laws that kept blacks and some poor whites from the polls. Without the right to vote, African Americans could not serve on juries or be elected to positions like justice of the peace and sheriff. Whites who committed crimes against blacks often did so with impunity.

Economic Recession 1918–1921

Chapter five

One of the most flagrant miscarriages of justice occurred during World War II. The Government forced over 100,000 Japanese Americans into internment camps and held them for years without filing criminal charges. Also, although lynching declined, perpetrators of violence against African Americans were rarely punished, while many African Americans were unjustly convicted of various crimes.

World War II 1942–1945

Chapter six

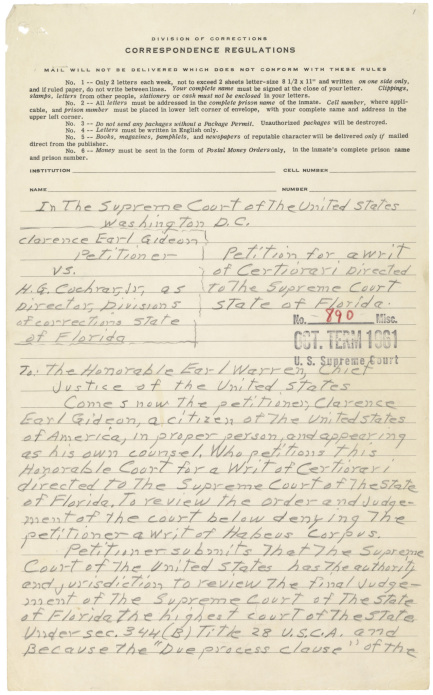

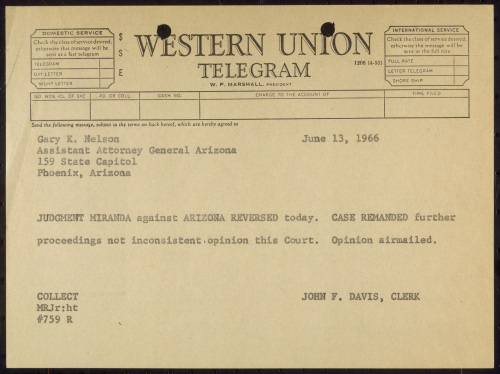

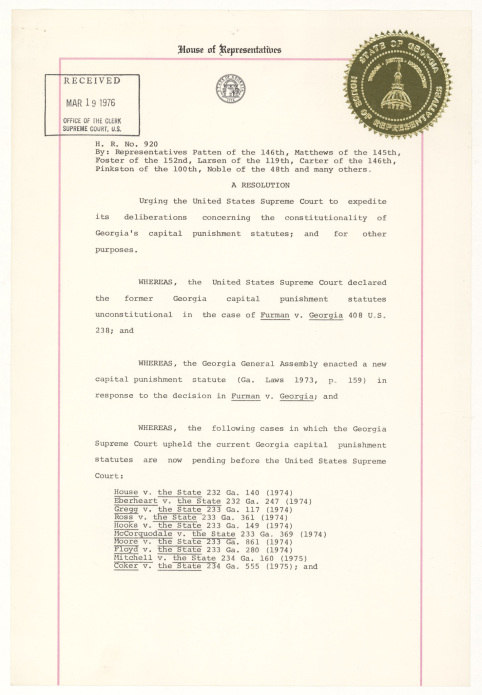

In the 1960s, Supreme Court Chief Justice Earl Warren presided over a series of decisions that helped to ensure that the rights contained in the Fifth, Sixth, and Eighth Amendments were extended to all individuals accused of criminal acts. In the years that followed his retirement in 1969, the political mood of the country became more conservative, and legislation began to focus on crime control.

The “People’s Court” 1961–1967

What about contemporary Issues?

Most of the records in "Records of Rights" were created before 1980 because the National Archives generally receives permanent records when they are 30 years old or older. Prior to that, they are maintained by the federal agency that created them.