Rights of Native Americans

Rights of Native Americans

The history of Native American rights is not a progressive march; it’s a story of rights being alternately acknowledged and disregarded. In this struggle, tribes negotiated hundreds of treaties with the Federal Government. Nonetheless, Native Americans lost many rights due to conflicts with Americans and the interests of the Federal Government.

THIS SECTION INCLUDES STORIES ABOUT STRUGGLES FOR:

- Recognition of tribal sovereignty

- Protection of land rights

- Survival of indigenous culture

Chapter one

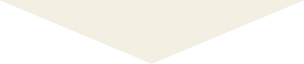

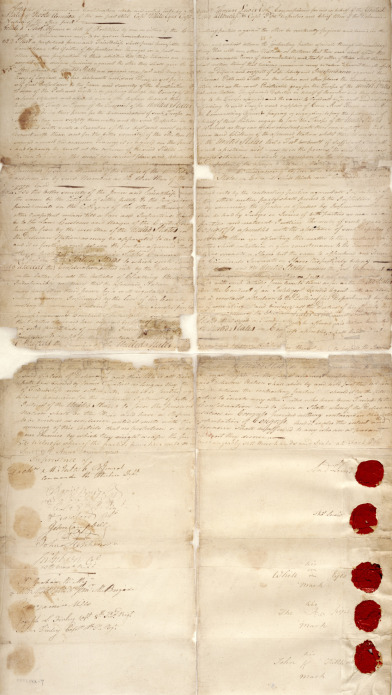

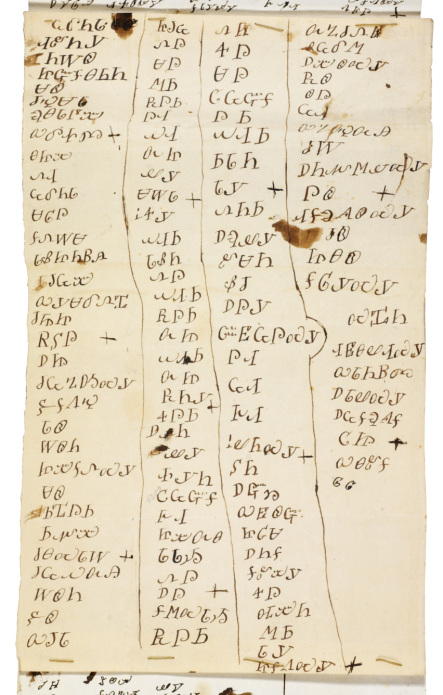

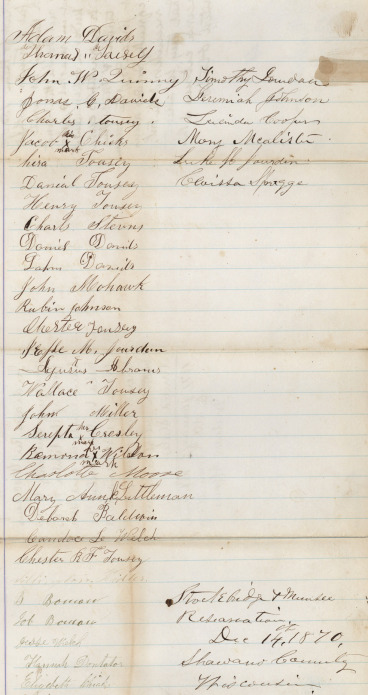

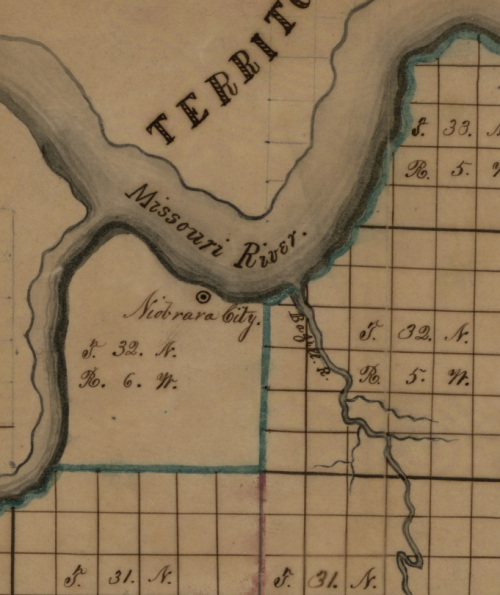

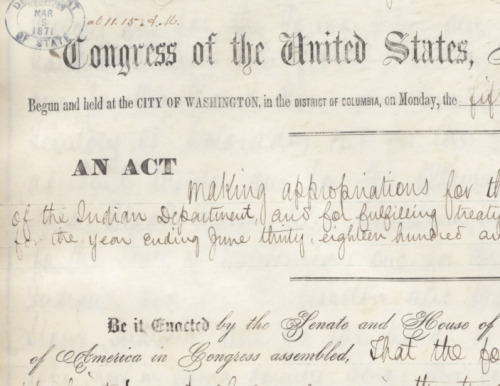

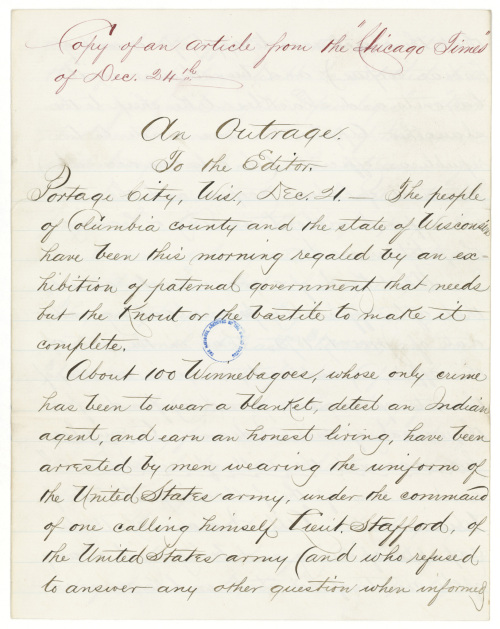

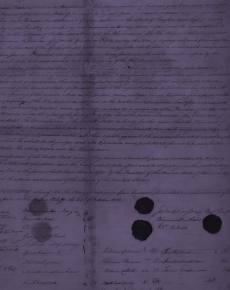

The new United States continued the Colonial-era practice of signing treaties with tribes to maintain peace between nations. But thirst for Native American land proved stronger than Government promises. Native Americans called treaties “talking leaves” that blew away as easily as leaves in the wind. The United States formally ended the policy of treaty-making with tribes in 1871.

Mounting Treaty Violations 1812–1860

The War of 1812 1812–1815

Chapter two

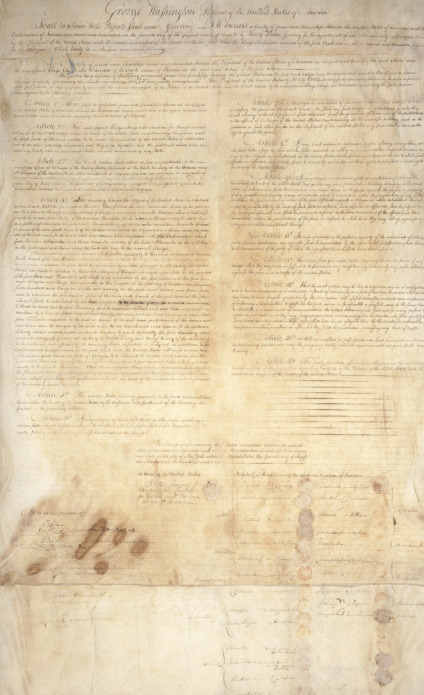

Prior to 1830, most Eastern Native American tribes remained east of the Mississippi River. Some tribes attempted to assimilate, in the hope that they could remain on their ancestral homeland. However, the demands of the expanding United States would lead to a shift in Federal Indian policy that favored removal of tribes West of the Mississippi.

Chapter three

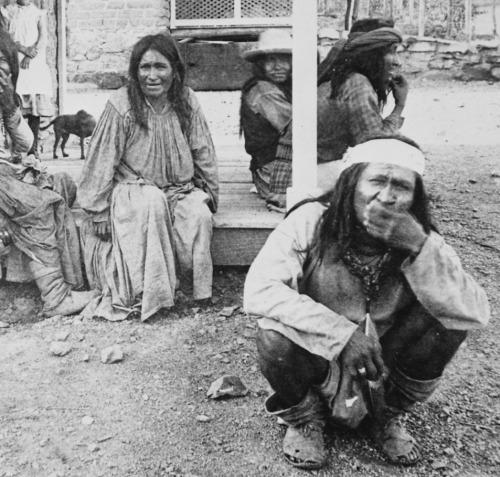

The Government moved Native Americans from their homelands—largely against their will—onto reservations west of the Mississippi to make way for expanding settlement. Native Americans were generally unsuccessful in their fight to protect their rights reserved through treaties, their land from further encroachment, and their culture from Euro-American influence.

Chapter four

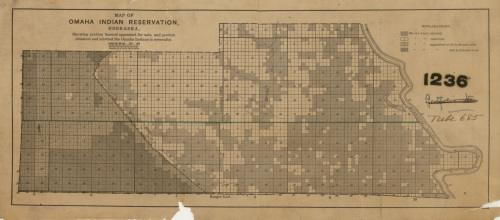

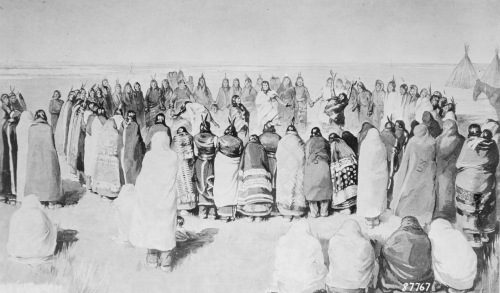

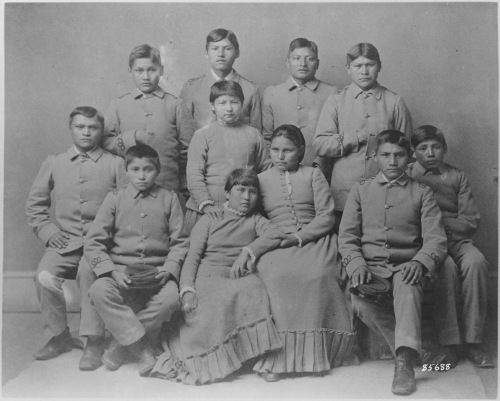

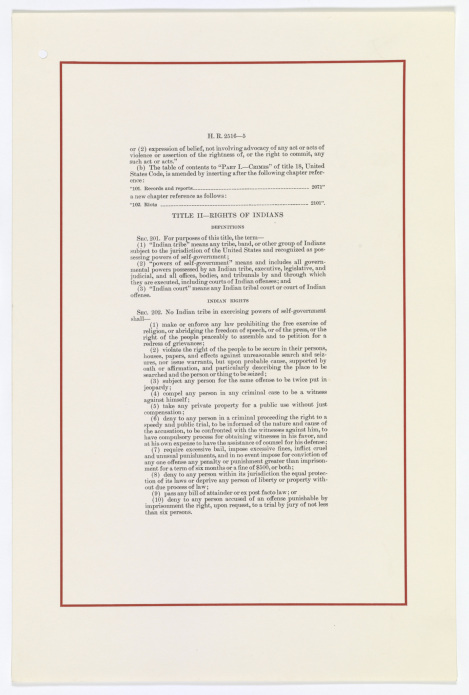

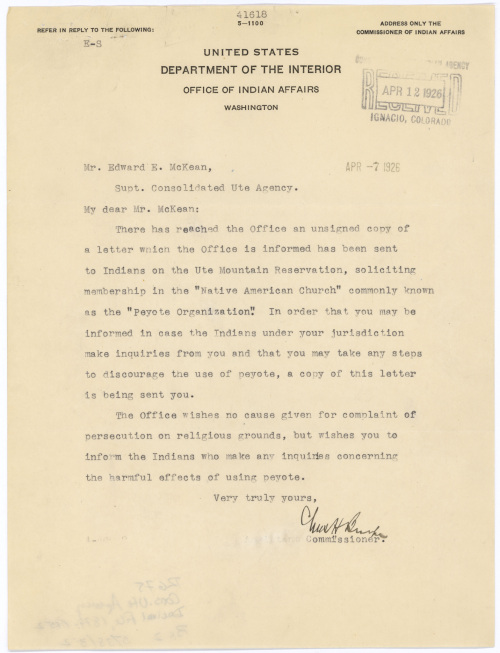

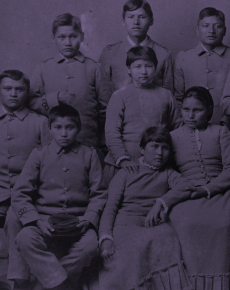

The Dawes Act sought to assimilate Native Americans through establishment of individual land ownership. The act banned traditional cultural and religious practices and established compulsory English and Christian children’s education. The effects of the Dawes Act were negative and enduring—it damaged tribal affiliations, familial and societal roles, and the economic standing of Native Americans.

Chapter five

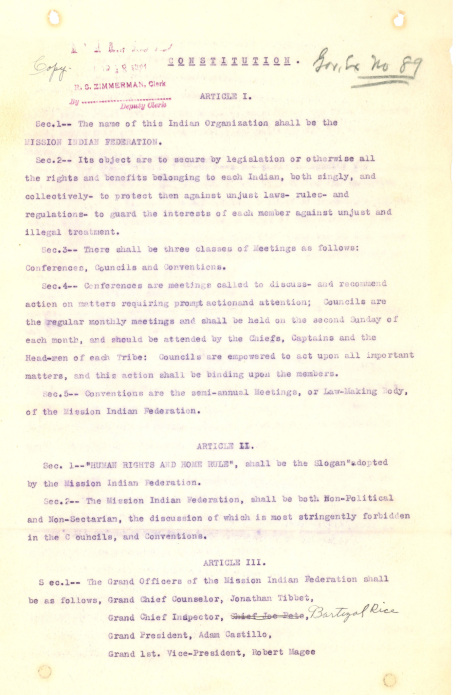

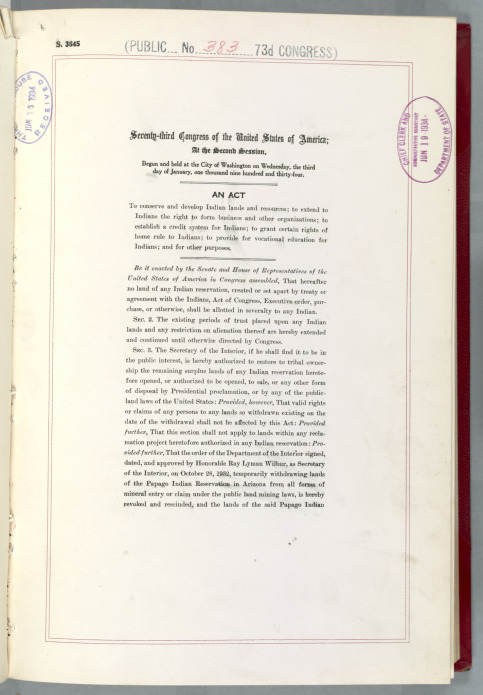

Following a privately funded 1928 report detailing the deplorable conditions of most Native Americans, Government officials concluded that the assimilation policy had failed. They reversed Federal Indian policy with legislation that ended the division of tribal lands and recognized tribal sovereignty. These changes enabled Native Americans to regain some power over their lives and tribal affairs.

World War I 1917–1918

The Great Depression 1929–1938

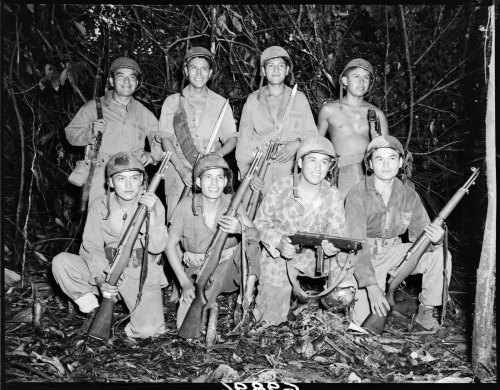

World War II 1941–1945

Chapter six

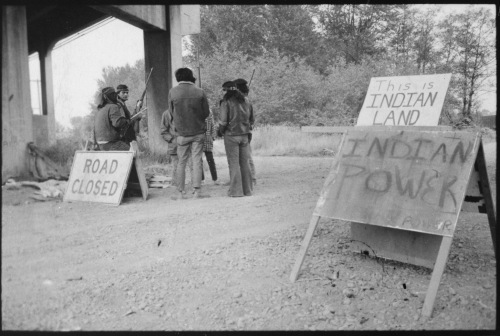

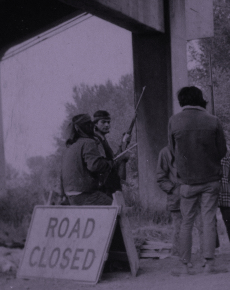

The termination policy of the 1950s ended Federal recognition of tribal sovereignty and Federal benefits secured through treaties. In the 1970s, Native American protests against the policy and centuries of injustices led the Government to shift its Federal Indian policy to one of self-determination—recognition of the right of tribal governments to manage their own affairs.

Television 1950–2013

Social Movements of the 60s and 70s 1960–1975

What about contemporary Issues?

Most of the records in "Records of Rights" were created before 1980 because the National Archives generally receives permanent records when they are 30 years old or older. Prior to that, they are maintained by the federal agency that created them.